2020 started as a rather exciting year for pit firing at Wytham Woods, Oxfordshire, with multiple firings scheduled and a steady flow of potters interested to join us in our work. My friend Jo Marshall (Moon Hare Ceramics) and I built a dedicated pit site in September 2019 with the help of Peter Hommel (Oxford University Archaeology Dept), Robin Wilson (Oxford Anagama Project Director) and Geoff Jones, with the aim to offer practical research facilities to archaeology students, and also to promote pit firing to other potters. Covid-19 pandemic happened and all was cancelled for the time being. I thought it would be interesting to reflect on the role of pit fired pottery in our modern society but also its value in the ceramics world as functional art.

The most ancient and primitive ways of firing clay (pit firing and mound firing) remain a strong artisanal activity in West Africa and South America.

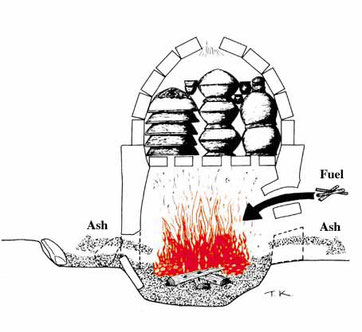

Mound kiln firing in Mali from 'African Pottery Forming and Firing' documentary by Christopher Roy

Pit fired pottery was produced for at least 25,000 years (the oldest evidence of pit fired pottery dating back as far as 29,000 BCE) before the discovery of earliest known kiln, which dates to around 6000 BCE (Yarim Tepe site in modern Iraq). It is easy to see the evolution of kilns from pit firing in tranches to chambers within the pit, risen structures above ground, and manufacturing needs requiring stronger structures which can be reused and refilled quickly.

An interesting article on primitive neolithic kilns is freely available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4894/708fa1eebc4a6939fc030e8f8f68d59f7e3d.pdf

Whereas pit firing can steadily sustain temperatures as high as 870°C, Neolithic kilns were able to go beyond 900°C. Potters switched to kiln firing as they were then able to fuse and form glass (and metallic oxides on its surface), cast and work metal, produced glazed and waterproof ceramics, smelt ores, dry grains and flowers (food/beverage production), and manufacture in large scale (brickwork, lime and charcoal).

Reconstruction of a beehive kiln, 4000BC, Tell Kosak Shamali (Syria)

Despite the benefits of kilns, open firing of ceramics still presents many advantages: the low temperatures and short firing times (average of 2 hours, 18 hours cooling) means a quick turnover for production of basic ware, and it also requires a small amount of combustible materials thus a reduced impact on the environment when compared to traditional wood firing kilns (48+ hours plus cooling time).

Ceramic wares are conventionally required to be fully waterproof, glazed on the inside and fired at high temperature for resistance to breakage and durability of use. This meant pit fired ceramics have been relegated to a decorative role. And although potters have since then pursued attractive qualities such as elaborate surface decoration and complex staining from the firing, the rudimentary utilitarian function of pit fired pots was pretty much lost in the western world.

Utilitarian pit fired pottery is still produced and widely used in places like Mexico and Mali, mainly as cooking vessels for stews or breathable food storage, so could we argue such a similar production might be a viable route for open fire potters? The specificity of the clay selected for such purpose is a crucial factor in my opinion.

Whereas the vast majority of pit fired pots in the western world are now stoneware (sometimes porcelain is also used), with a small amount of mica or quartz, and a coarse texture to enable heat expansion, Mexican and West African potters use micaceous clay. This type of body contains tiny but abundant flakes of a sheet silicate called mica, one of the most widely distributed minerals around the world, generally occurring in inigneous, sedimentary and certain metamorphic rocks. Stable when exposed to light, moisture and extreme temperatures, mica strengthens the clay body whilst insulating the ceramic walls of the cooking ware, which makes it a very valuable element of the clay body, even at the low temperatures of pit and mound firings. In contrast, stoneware and other grogged bodies with a relatively small amount of mica, when fired at the same low temperatures, would not be able to sustain thermal shock if used on naked flames.

Micaceous cookware by Marc Millovich

The benefits of cooking in clay pots are notable and widely accepted: the clay body will bring key nutrients such as calcium, phosphorous, iron, magnesium and sulphur to the cooked food. Clay is also alkaline, neutralising acidity in the food, which helps digestion. So could we see a potential revival (even if small) in European countries of such low fired pottery for cooking? As long as micaceous clay is used, I would be very keen to see such production evolve and further inspire potters to make new forms and develop functional art. This would certainly be an interesting path to explore at our site in Wytham Woods.

However, if one wishes to remain fully sustainable in the creation of cooking ware in pit fired pottery, the main problem would be the local sourcing of a good micaceous clay, which requires a substantial presence of mica in argillaceous sediments in the Jurassic strata of the British Isles. I do not have yet the necessary geological information to answer that question.